Synonyms: Parturient paresis, Post Parturient Hypocalcemia, parturient apoplexy, paresis puerperalis

Introduction:

It is a metabolic disorder that affects adult dairy cows and buffaloes usually around the time of parturition or within 72 hours of parturition arising because of disordered homeorhetic change, characterized by acute to per acute, flaccid paralysis. Sternal and lateral recumbency, circulatory collapse are also clinical indicators.

Etiology:

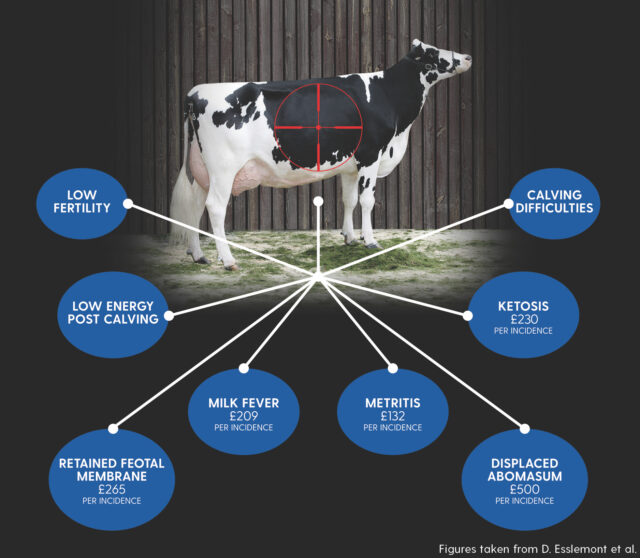

According to Shank et al. (1981), Curtis et al. (1985), Stevenson and Lean (1998), there is a significantly increased risk of disease during the periparturient or transition phase, which lasts for 4 weeks before and 4 weeks after calving. According to Bauman and Currie (1980), this period is characterized by a sequence of homeorhetic adjustments to the needs of lactation. Homeorhetic processes involve a planned series of metabolic changes that enable an animal to adjust to the difficulties of the altered state. Hypocalcemia is one of the issues brought on by unbalanced homeorhetic change, which reflects unbalanced homeostasis. Hence, Hypocalcemia is the main contributing factor in the etiology of Parturient paresis. Bone, intestine, liver, kidney, endocrine glands, adipose tissue, and mammary gland are the target organs most linked to calcium homeostasis. The disparity between fetal and lactational calcium requirements poses a challenge to calcium homeostasis during the process of homeostatic adaptation to lactation. The discrepancy between the 13 to 18 g of calcium released in colostrum or milk and the 5.3 g daily fetal drain can be more than the combined quantity of calcium in plasma and interstitial fluid (between 6 and 10 g). This discrepancy must be balanced by either increasing the amount of calcium that enters the bloodstream by gastrointestinal absorption or bone resorption, or decreasing the amount of endogenous fecal calcium that leaves the body through routes other than milk. Milk fever like conditions arise in cases where there is excessive drain or loss of calcium through colostrum and milk and the body cannot mobilise enough calcium from bone due to the excessive losses of calcium through colostrum (2.3 g/kg) and milk (1.2 g/kg) (Bhikane et al., 2004; Radostits et al., 2007) along with reduced intestinal absorption of calcium during pregnancy due to starvation or reduced feed intake throughout pregnancy or at the time of delivery or digestive disorders like intestinal illnesses, ruminal atony, and indigestion reduce absorption. Slow mobilization of Ca from bone / skeleton due to Parathormone deficiency, high calcitonin in blood and Vitamin D3 deficiency are other factors contributing to disruption of Ca- homeostasis.

Dietary Factors:

The calcium homeostatic mechanism is suppressed by a high calcium diet during pregnancy. Such animals are more prone to severe Hypocalcemia just after delivery because they are unable to start calcium resorption from bone or boost intestine absorption. A high-phosphorus diet during pregnancy inhibits the renal enzyme that is responsible for formation of 1,25-(OH)2D, which is catalyzed by the enzyme, resulting in reduction of intestinal calcium absorption.

An unhealthy calcium-to-phosphorus ratio in the diet i.e., and highly alkaline diet for e.g., legumes and excessive intake of oxalates and phytates can also be predisposing factors of this disease.

Clinical Signs:

There are three distinct stages to parturient paresis.

Stage 1: Animals are mobile but exhibit hypersensitivity and excitability. The triceps and flanks of cows may tremble slightly. The animal is reluctant to move and frequently consumes less or no feed. A small head shake, tongue sticking out, and teeth grinding are possible symptoms. Normal to slightly over normal rectal temperature; the skin may feel cold to the touch. The animal has an ataxic appearance, abnormal gait and falls frequently. A close inspection reveals agalactia and rumen stasis. A normal heartbeat and normal breathing patterns are also possible. Cows are likely to advance to the second, more severe stage if calcium therapy is not started.

Stage 2: Sternal recumbency and lowered consciousness are the characteristics of the second stage. The cow seems drowsy in sternal recumbency, typically with a lateral bend in the neck or the head turned into the flank. Some of these cows may exhibit behavioral changes like nervousness and fright when approached. Tetany of the limbs that was present in the first stage disappears in this stage. The skin and extremities are cold, dry muzzle and the rectal temperature is subnormal (between 36 and 38°C, or 97 and 101°F) tachycardia with indistinct murmuring of heart. It is challenging to raise the jugular veins since the venous pressure is low and the arterial pulse is weak. The respirations are not significantly altered, however occasionally a slight forced grunt or groan is discernible. Constipation is a common distinctive symptom, as is ruminal stasis and secondary bloat.

Stage 3: Diminished responsiveness to any external stimuli or even comatose cow in lateral recumbency is a hallmark of the third stage, animal is unable to assume sternal recumbency without support. The cardiovascular system and temperature depression are more pronounced. The pulse is virtually impalpable, the heart rate is up to 120 bpm, the heart noises are almost inaudible, and it can be impossible to lift the jugular veins. Bloat is frequently caused by lateral recumbency and protracted rumen stasis. Without care, some animals persist unchanged for several hours, but the majority deteriorate over several hours until passing away silently from shock in a state of total collapse.

When hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia co-exist, the clinical consequence will be tetany and hyperesthesia past the point of initial excitation. The eyelids could twitch fibrilarly. Most non parturient milk fever cases respond to calcium medication, but if the fundamental root cause is not treated, they may reoccur.

Diagnosis:

•Based on characteristics clinical signs like sternal or lateral recumbency and history of age, parturition and milk output, exposure to cold stress and transportation or inefficient ruminal activities or in certain cases history of access to plant rich in oxalates like spinach, beet greens, rhubarb, Swiss chard, parsley, purslane, and certain types of nuts such as almonds and cashews.

•Clinical pathology – a) low Serum Ca, P, glucose, and high serum Mg levels

b) Ca: P ratio decreases to 1:1 from 2:1 and Ca: Mg ratio decreases to 2:1 from 4:1

c) Urine analysis – the calcium precipitation test is usually negative.

•Observe the cow’s reaction to the Ca therapy, searching for symptom improvement like salivation, eructation, occurrence of defecation, urination and rumination and indications of better muscular tone.

Differential diagnosis:

1) Subclinical Hypocalcemia – no clinical signs like lateral kink of neck, downer cow, lethargy, cold extremities, rumen atony etc.

Blood calcium concentration reaches levels even lower than their baseline six hours after treatment.

2)Ketosis – animal respond to Ca therapy (stands up quickly) but signs of ketosis persist

3) Hypomagnesemia – low serum Mg (<1.2mg/dl), response to IV Mg injection recorded within 20 minutes.

4) Degenerative myopathy- No response to Ca therapy, SGOT levels are high.

5)Botulism – in any sex at any age and no response to Ca therapy

6)Retained placenta – in case of toxemia may die if treated with Ca or Mg salts.

Treatment:

It’s ideal to start treatment during the first stage itself as long delay can lead to ischemic muscle necrosis.

- Parenteral injection of Calcium borogluconate is the standard practice of management of Hypocalcemia during milk fever.

Dose & Route: Ca-borogluconate (18-25%) @ 450ml /kg body weight (250ml IV- & 200-ml SC to avoid Ca toxicity) in cattle for at least 30 minutes.

Sheep & Goat- 25-50 ml/kg body weight slow IV

•Ca-gluconate cause less tissue irritation than Ca borogluconate

• To counteract Ca++ toxicity, MgSO4 10% @ 200-400ml is given either IV or Subcutaneously.

• Slow administration of Ca injection is recommended (rat Xe – 10-20 drop/minute)

2. Monitor Vital Signs:

– Monitor heart rate, respiration rate, and body temperature, with signs of dysrhythmia therapy should be stopped.

Atropine Sulphate- @0.02-0.2 mg/kg body weight is administered in case of bradycardia.

3. Oral Calcium Supplementation:

– Calcium Gel/Bolus/Drench

– Dosage: 150-200 gm

– Administered after IV treatment

– Continue for 2-3 days in case of severe milk fever

4. Electrolyte Balance:

Fluid therapy (Ringer’s lactate, DNS @10-15ml/kg)

5. Supportive Care:

Inj. vit D3 @ 10 million unit i.e., 1 million units / 45 kg body weight I/M one week before calving

6. Phosphorus injection: inj URIMIN @10-15ml in cattle in cases when Hypocalcemia is associated with Hypophosphatemia

Prevention &Control:

•A diet high in calcium during pregnancy may make the cow more susceptible to milk fever. Additionally, a high phosphorus diet during late pregnancy increases the likelihood of developing milk fever. The chances of milk fever is thought to be reduced by keeping the Ca: P ratio in feed during the final month of gestation at 1:3.3.

However, it is established that a low calcium diet during early pregnancy and a high calcium diet before parturition significantly reduce the incidences of milk fever.

•Calcium injections given as a preventative soon after calving are efficacious.

• Feeding of Forage crops like alfalfa, clover, or kale, as well as grains like barley and oats containing high levels of anions (Sulphur& chloride) are evident to have a minimizing role in inducing milk fever over diet containing greater level of cations (Sodium & Potassium) since excess anions help in calcium absorption.

• NH4Cl @25 gm orally during last few weeks of gestation and @100 gm/day at the time of parturition helps in producing acidosis which further helps in the enhancement of blood calcium metabolism.

• To prevent over or under acidification that could cause problems in the blood calcium metabolism, cation anion diets or the use of ammonium chloride in diets should be monitored by tracking the Ph of urine.

•Vitamin D supplementation: A practice by some farms is supplementing high amounts of vitamin D to pre partum dry cows in the feed. These vitamin D doses pharmacologically increased intestinal Ca++ absorption.

•Achieving the correct body condition score at calving and dry period is critical for the prevention of milk fever.

• Farmers are to be advised to avoid suckling by young ones or milking for 3 days after treatment.

• Avoid Cold stress conditions by proper sheltering to the lactating or pregnant animals.

• Travelling large distances is to be avoided during pregnancy

• The animal is to be kept at strict surveillance 48 hours prior to calving and 48 hours following calving and any early signs should be checked

•To encourage rumen contractions because concentration causes stasis, give roughages to animals that are about to give birth.

References:

•Bauman, D.E., Currie, W.B., 1980. Partitioning of nutrients during pregnancy and lactation: a review of mechanism involving homeostasis and homeorhesis. Journal of Dairy Science 63, 1514–1529.

•Curtis, C.R., Erb, E.H., Sniffen, C.J., 1983. Association of parturient hypocalcemia with eight periparturient disorders in Holstein cows.

Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 183, 559.

•Shank, R.D., Freeman, A.E., Dickinson, F.N., 1981. Postpartum distribution of costs and disorders of health. Journal of Dairy Science 64,683–688.

•Stevenson, M.A., Lean, I.J., 1998. Descriptive epidemiological study on culling and deaths in eight dairy herds. Australian Veterinary Journal 76, 482–488.

• Finbar M,Luke O, Desmond R, Michael D. Production diseases of transition cow: Milk fever & Subclinical hypocalcemia. Irish Veterinary Journal.2006; 59.

• Bhikane, A.U., Anantwar, L.G., Bhokre, A.P. and

Narladkar, B.W. 2004. Incidence, ClinicoPathology and Treatment of Milk fever in Cattles.

Simran jeet Singh1, Aditya Kumar2*, Aprajita Johri3 and Aditi Kuriyal4

¹PG Scholar, Department of Veterinary Medicine

2,3PhD Scholar, Department of Veterinary Medicine

4UG Scholar

College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences

G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, Uttarakhand, India- 263145

Corresponding author mail- adityakumar1696@gmail.com