Introduction: The process of parturition is a critical and often miraculous event in the animal kingdom. However, complications can arise, and one such challenge is the retention of the placenta. This problem is more seen in dairy animals. After 2-6 hours of parturition placenta expels out. When the fetal membranes does not expel naturally till 24 hours then this condition is called retention of placenta. This condition is not only discomforting for the animal but also poses significant health risks. In this article, we will explore the causes, implications, and potential solutions for retained placenta in animals.

Causes of Retained Placenta:

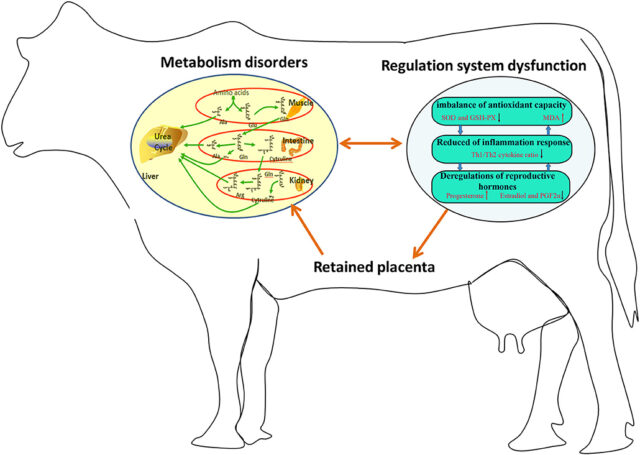

Hormonal Imbalances: Hormonal changes are essential to the birthing process. The placenta may be retained if there are any changes to the delicate hormonal balance that governs labor and the postpartum period.

Dystocia (Difficult Birth):The placenta may remain in the body if delivery of fetus is difficult or takes a long time. The fetus size, anatomical anomalies, or incorrect placement during birth might all be the cause of this.

Metabolic Disorders: Animals suffering from underlying metabolic abnormalities, such as hypocalcemia (low calcium levels), may find it difficult to contract their uterus, which might result in the placenta being retained.

Nutritional imbalance: Deficiency of vitamin A and mineral like selenium in animal diet also contribute for occurrence of this condition.

Implications of Retained Placenta:

Infection Risk: Retained placenta provides a perfect habitat for bacterial development. The danger of infection increases with the length of time the placenta stays in the uterus. The animal’s general health may be harmed and systemic problems may result from this.

Uterine Complications: Long-term placental retention may harm the uterus and result in conditions like endometritis or metritis, which may affect the animal’s ability to reproduce in the future.

Reduced Milk Production: Retained placenta can disrupt the hormonal balance necessary for proper lactation. This may result in reduced milk production, affecting the health and growth of the newborn.

Solutions and Management:

Veterinary Intervention: Timely veterinary assistance is crucial when an animal experiences retained placenta. A veterinarian can assess the situation, administer appropriate medications, and, in severe cases, manually remove the retained placenta.

Hormonal Therapies: Hormonal treatments may be recommended to regulate hormonal imbalances and stimulate uterine contractions, facilitating the expulsion of the placenta.

Proper Nutrition and Management: Maintaining optimal nutrition and ensuring a stress-free environment for pregnant animals can contribute to reducing the risk of retained placenta. Adequate calcium supplementation and a well-balanced diet are essential.

Regular Monitoring: Regular monitoring during pregnancy and birthing is essential for early detection of potential complications. This allows for timely intervention and reduces the likelihood of retained placenta.

Treatment:

Manual removal of placenta: A variety of methods have been used in the treatment of bovine RFM, although the efficacy of many of these treatments is questionable. Manual removal of the placenta remains a common practice despite numerous studies that fail to demonstrate a beneficial effect on reproductive performance or milk yield. Manual removal can result in more frequent and severe uterine infections, when compared with more conservative treatment.

Antimicrobial therapy: The use of antimicrobial therapy in the treatment of RFM has demonstrated conflicting results. Postpartum metritis is a common sequelae of RFM, and the rationale behind antibiotics for RFM is to prevent or treat metritis and its subsequent negative effects on fertility. Local antimicrobials, typically given as uterine infusions or boluses, have not been shown to reduce the incidence of metritis or improve fertility.

Hormonal therapy: The most commonly used hormone products in treating RFM are prostaglandins and oxytocin. These hormones play a role in uterine contraction, and could be effective in treating RFM because of uterine atony. However, it is thought that uterine atony accounts for a very small percentage of retained placenta cases and numerous studies have not supported their use as a general treatment for RFM.

Collagenase role: The breakdown of collagen plays a role in placental detachment, and infusion of collagenase can be helpful in breaking the caruncle-cotyledon bond in RFM. Injection of 1 L of saline containing 200,000 IU of bacterial collagenase into the umbilical arteries of retained placentas caused earlier placental release than untreated contemporaries. This treatment is targeted specifically at correcting the lack of cotyledon proteolysis and might be more effective than traditional therapies.

Conclusion:

Animals with retained placentas have a difficult condition that has to be treated right away. For the sake of her children and herself, it is imperative to identify the reasons, examine the consequences, and put workable remedies in place. We may reduce the risks of retained placenta by effective veterinarian treatment, hormone control, and careful husbandry techniques, resulting in a better and safer birthing experience for animals in our care.