Abstract

Sheep, unlike most domestic livestock species, is well-known for having a distinct season of breeding activity. The annual cycle of daily photoperiod has been identified as the determinant factor, whereas environmental temperature, nutritional status, social interactions, lambing date, and lactation period have been identified as modulators. The purpose of this paper is to summarize what is currently known about sheep reproductive seasonality. The paper covers the symptoms of seasonality in both the ram and the ewe after discussing the necessity of seasonal breeding as a reproductive strategy for the survival of species. The neuroendocrine basis of photoperiodic regulation of seasonal breeding is studied in-depth, with a focus on determining and modifying elements.

Introduction

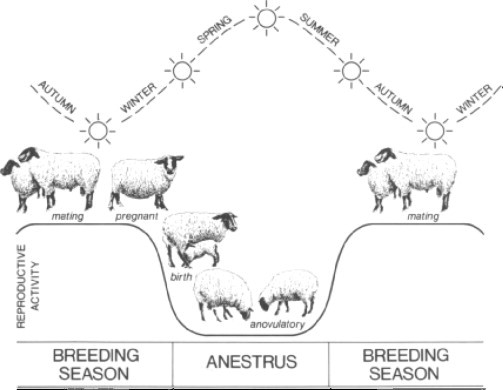

Natural selection pressure has favored the dissemination of genes that link birth time to the most appropriate period of the yearly climatic and food availability cycles, i.e., early spring (Jewell et al., 1974; Ortavant et al., 1985; Short 1985). Sheep are generally known as animals with marked seasonality in breeding activity, unlike most domestic livestock species. This phenomenon’s determining factor has been discovered as the daily photoperiod’s annual cycle, while environmental temperature, dietary status, and social interactions may influence it.

Normal breeding habits of Sheep:

- Age of Puberty- Typically, ewes reach puberty at 5 to 12 months, depending on breed, nutrition, and date of birth.

- Anestrus Period- This is the time of year when ewes do not generally show signs of estrus (heat). In ewes, there are three types of anestrous: seasonal (affected by the length of the day), lactation (affected by the sucking stimulus of lambs), and postpartum. The normal duration for ewes is approximately 17 days between heat periods. However, it can vary from 14 to 19 days. The heat period usually lasts 30 to 35 h, with a range of 20 to 42 hours with the ovulation late in the period.

- Gestation Period- Ewes have a usual gestation length of 147 days, with a range of 144 to 152 days. The gestation period of medium-wool breeds and meat-type breeds is usually shorter than that of fine-wool breeds. High temperatures and a lack of nutrients can cut the gestation time by two or three days. Ewes bred to white-faced wool-breed rams may have a somewhat longer gestation time than ewes bred to meat-type rams.

Breeding ewe lambs- Ewe lambs that breed and lamb as yearlings have a higher lifetime production than ewe lambs who have their first lamb when they are two years old. Because the beginning of puberty is mostly determined by body weight, ewe lambs should be fed enough to reach at least two-thirds of maturity weight before breeding. Separate yearling sheep from mature ewes and feed them separately so that the yearling ewes can reach their full potential size.

Effect of environment

- Sheep’s sexual activity is mostly influenced by the light-to-dark ratio. As the days get shorter, estrus becomes more common. In general, ewes bred in September, October, or November have the highest fertility and efficiency; ewes bred at this time have the highest percentage of multiple births.

- Fertility, embryo survival, and fetal growth are all affected negatively by high temperatures. This is the most powerful barrier to fall lamb production. High temperatures during breeding can limit the rate of conception. Heat stress during pregnancy affects fetal growth resulting in smaller lambs at birth.

Managemental methods to optimize breeding

- Estrus stimulation- It is the practice of putting vasectomized males with females about 10 to 2 weeks before the start of breeding to stimulate and synchronize breeding. As a result, a significant number of ewes will ovulate and conceive during the early part of the breeding season.

- Oestrous synchronization- The estrous cycle in ewes is synchronized so that a significant number of them are in heat at the same time. This would help to lower the expense of artificial insemination or natural breeding, as well as the associated lambing care. It produces consistent flocks of lambs, making disposal easier and allowing for higher prices.

- Ram effect – Sudden introduction of ram in the ewes flock after prolonged separation bring more number of ewes into estrous.

- Telescoping- After a separation of two-to-three-month, the ram is re-introduced to the flock. In the first estrous cycle, 70 to 80 percent of ewes will be in heat due to the sudden introduction of a ram into the sheep flock.

- Hormonal method- Progesterone hormones or analogs are administered through feed, implant, or impregnated vaginal sponges. The hormone is removed after 14 days of treatment. Within three days, the animal comes in heat. All of the animals come in heat within 72 to 96 h after receiving two intramuscular injections of prostaglandin F2 alpha or its synthetic analogs at 10-day intervals.

Conclusion:

The seasonal anestrus is a phenomenon affecting the normal reproductive life of the animal mainly the farm animals which ultimately costs the livelihood of the farmers. The seasonal anestrus in the sheep rearing is a common problem faced by low-income farmers’ groups that costs them a lot affecting their livelihood. This problem can be managed by the managemental as well as therapeutic aspects. The managemental aspect includes several practices such as estrus stimulation, estrus synchronization, ram effect, etc. that are cost-effective as well as effective also. The hormonal approach is slightly costly but more effective than the natural behavioral effect. The sheep owners should have to follow the above practices to get benefit from them.

Authors: Sujata Jinagal1, Upender2*, Suvidhi3

1M.V.Sc. Scholar, Department of Veterinary Gynaecology and Obstetrics,

Lala Lajpat Rai University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Hisar, 125004.

2*M.V.Sc Scholar, Division of Veterinary Public Health & Epidemiology,

ICAR-IVRI, Izatnagar, U.P., 243122.

3Senior Research Fellow, ICAR-NRCE, Hisar, 125001.

*Corresponding author: yadavupender10@gmail.com